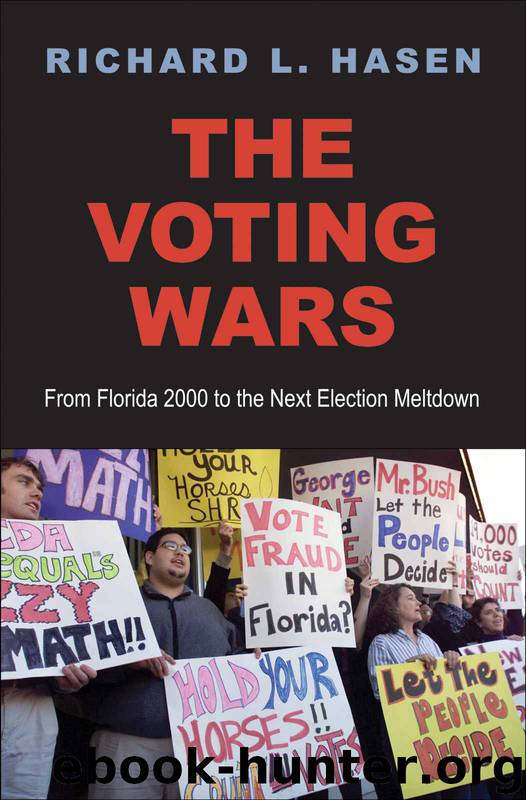

The Voting Wars: From Florida 2000 to the Next Election Meltdown by Hasen Richard L

Author:Hasen, Richard L. [Hasen, Richard L.]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2012-08-02T00:00:00+00:00

5

Margin of Litigation

The morning after Election Day in 2008, Norm Coleman faced a tough question from reporter Curt Brown of the Minneapolis news paper the Star Tribune. “If you were down by 725 [votes], would you say forget it and save the taxpayers’ money?”1

It is a question no candidate slightly ahead of a competitor wants to answer. Although the public accepts election totals as they come in on election night as an accurate representation of the truth, such numbers are usually wrong and almost always incomplete. In the rush to get everything done on Election Night, election officials sometimes misreport numbers or, as we saw in the Wisconsin Supreme Court race, even forget to report totals from entire towns. It takes days for officials to verify and recheck the numbers. Many states also have absentee ballots to process and count, and now, in part thanks to the Help America Vote Act, there are often piles of provisional ballots to consider.

When the apparent winner is ahead by thousands of votes in a statewide race, and Election Day comes and goes with no reports of widespread problems or irregularities, it is usually safe for candidates to expect that the outcome will not change. Election officials then certify the results weeks later. But when the margin is closer, candidates concede or declare victory at their peril.

Remember Al Gore calling George W. Bush to retract his concession in November 2000, moments before Gore was to give his concession speech? Democrats were not going to make the same mistake twice. In 2004, John Kerry conceded in Ohio to George W. Bush only after Kerry’s lawyers satisfied themselves that the election was beyond “the margin of litigation”: the vote gap between the leading candidates was large enough that there was no point in contesting or litigating to a potentially better result.

Norm Coleman, the incumbent U.S. senator from Minnesota, didn’t declare victory in his race for reelection against Democratic challenger Al Franken and independent candidate Dean Barkley that morning, but he came close. Ahead by 725 votes over Franken, and much more over Barkley, Coleman expressed a confidence in the vote margin that would later come back to bite him: “Curt, to be honest, I’d step back…. I just think the need for a healing process is so important, the possibility of any change of this magnitude in the voting system we have is so remote, but that would be my judgment. I’m not … again, Mr. Franken will decide what Mr. Franken will do. But do I think under these circumstances it is important to come together? I do.”

Months later, after Franken took the lead following a recount and election contest, Coleman saw less need for “healing.” He contested and litigated all the way to the Minnesota Supreme Court, which ultimately voted unanimously to reject his challenge to Franken’s lead. Although the election was in November and the winner was supposed to be seated in January, the protracted legal battle meant that Minnesota was missing one of its two senators until July 2009, when Franken was at last sworn into office.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(18998)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12177)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8873)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6855)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6248)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5762)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5707)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5480)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5409)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5199)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5127)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5065)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4937)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4898)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4757)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4727)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4683)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4484)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4473)